Build Your Own Skiff Aluminum 98,Diy Canoe Kit Modeling,Byjus Maths Limits 80 - Try Out

Questions: Welded aluminum boatbuilding Building the 12 Foot Aluminum Skiff Kit from myboat090 boatplans myboat090 boatplans Aluminium jet boat build. Hace 6 anos.� Day 2 of the boat build shows us how hard it can be to build your own boat from a kit. There are some important challenges to How To Build a 27 Foot Aluminum Cabin Cruiser From a Kit. Pacific Boats create aluminum skiffs and workboats that are rugged, purpose built boats for commercial, government, or law enforcement. Learn more here! Why Pontoon Boats Are Sweeping the Country.� Build your own 12' X 4' Simple Aluminum Boat (DIY Plans) Fun to build! Save Money! My brother designed this Boat using ideas from the many boats being used around. Aluminium open dinghy with cross seats. Suitable rowing or with outboatd to 15 hp steering from back. Tough 2mm plate hull is easily constructed from plans. A very.� We do this with marketing and advertising partners (who may have their own information they�ve collected). Saying no will not stop you from seeing Etsy ads, but it may make them less relevant or more repetitive. Find out more in our Cookies & Similar Technologies Policy.

The number of people with aluminum welding skills and access to fabricating equipment has increased considerably over the years. Yet many are unaware of fundamental considerations confronting the short-handed amateur building a single boat for his own account. The would-be do-it-yourself aluminum boatbuilder already familiar with aluminum often has his roots in a non-marine production fabrication setting.

Thus there may be a tendency to want to apply mass-production techniques to the construction of just a single boat. But building a single boat yourself is considerably different from one built on a production line, and thus may require certain adjustments and even a revised mind set on the part of the builder.

First, there is no one, superior way to build an aluminum boat. In fact, there can be many suitable approaches and variations. Second, there is no reason why you can't build your own aluminum boat in your own garage or backyard that looks identical to one produced in a factory, and with similar weight and strength qualities even if you don't use the same mass production methods, or have access to sophisticated, specialized equipment and proprietary materials.

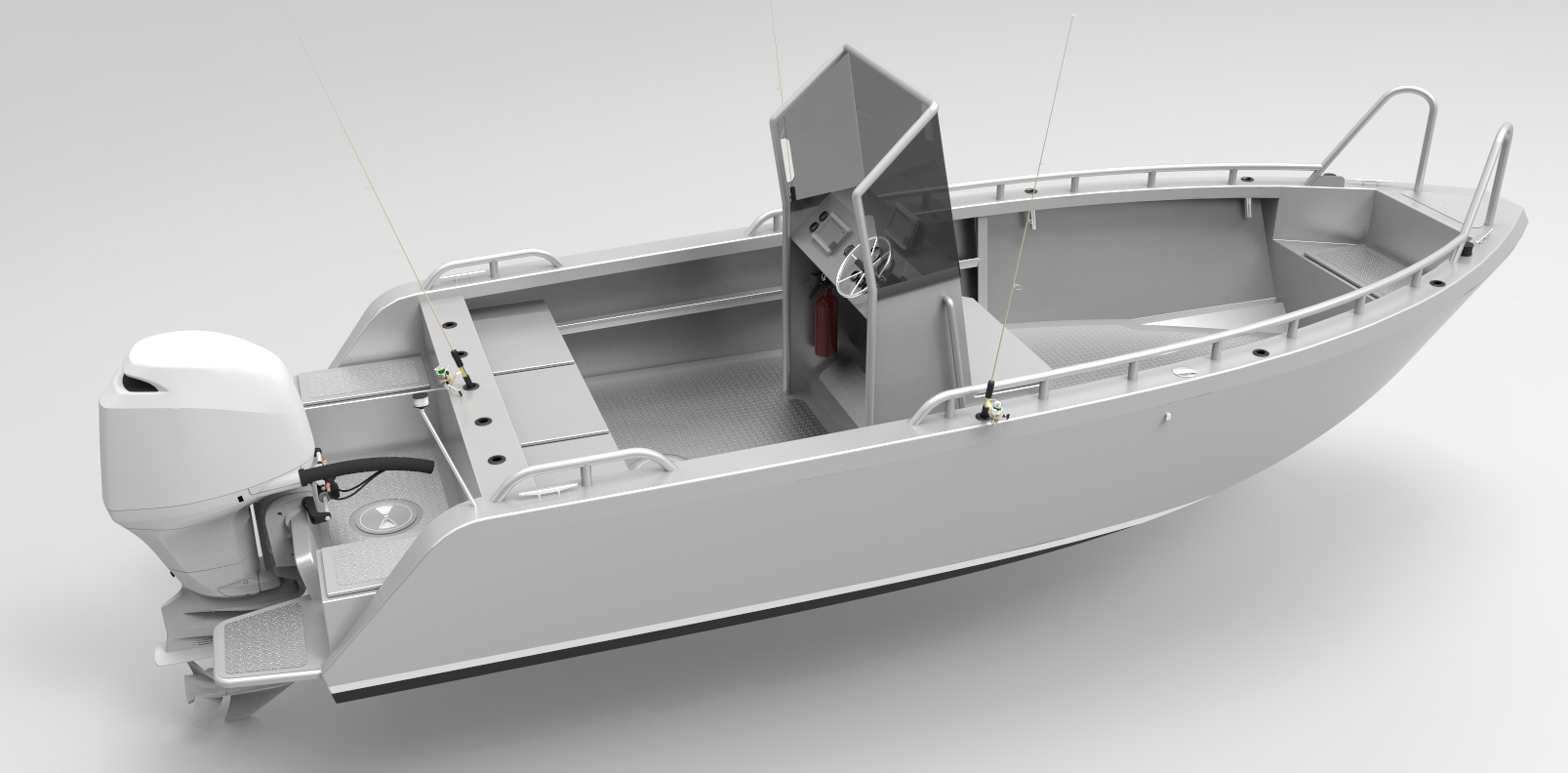

Consider the following. Because production builders are always thinking up ways to cut labor and material costs, and time required to build boats, they evolve specialized methods and materials that help toward these ends even if there is not necessarily any improvement in the boat itself. For example, they may use special proprietary extrusions to expedite some assembly process such as joining side and bottom plating at the chine see Fig.

But when building your own boat, you may not have access to such a specialized member, nor could afford it or the shipping in the small quantities you'll need even if available. Alternately, your chines might then be backed with a simple round bar Fig.

None of these methods is necessarily superior, but just different due to circumstances. Also, production builders often make up sophisticated re-usable production jigs over which pre-cut hull panels are assembled and welded first. These jigs may also rotate to facilitate high-speed welding, with internal members added after the hull is removed from the jig. But when building your own boat at home, it's just as likely that the boat's internal framework gets built and set up first, with plates fitted over this, marked to shape, cut to suit, and then welded in place after.

In other words, the boat's framework becomes the forming jig and stays in the boat; you make it and pay for it only once. In either case, end results are much the same and with comparable boat quality.

Using a frame substructure for setting up your hull has several advantages for the do-it-yourselfer typically working alone. First the frame substructure makes it easy to assure hull accuracy that is so important to ultimate performance in a powerboat.

Second, the framework makes it possible to build from "off-the-shelf" materials and shapes available anywhere for lower costs and easier material purchasing. Finally, the framework makes it easier to form hull members in place and during weld-up since clamps and other devices can be readily used most anywhere as required, acting as extra pairs of "helping hands" in the process.

Factory production boatbuilders often use specialized forming equipment not always available to amateurs, or use forming services that might be provided by metal suppliers when quantity requirements are high.

Conversely, a design for the do-it-yourself builder would more likely specify internal longitudinal stiffeners i. Either method gets the job done but the latter is easier and cheaper for most building their own boats. First, a disclaimer. But in reality few do-it-yourselfers want to pay the price for the service. But steel is considerably heavier than aluminum, so boats designed for steel are usually designed for greater displacement. Thus, if the boat is built from aluminum, it won't be nearly as heavy and may therefore float higher in the water.

The consequences for a semi- or full-planing powerboat might be so much the better since the lighter aluminum boat will need less power and fuel.

But in converting slower displacement-type powerboats from steel to Build Your Own Skiff Aluminum Zip aluminum, you might need to add ballast into such a boat done in aluminum to bring it back down to its original lines. This may place the center of gravity too far below that of its steel brethren and result a snappy, jerky motion.

So instead, you may want to place some of the added weight higher up. But again, best advice is to consult the boat's designer. Aluminum is not as strong as steel so some compensations must be made if using it in place of steel. Without getting too technical, with aluminum used for shell plating e. Put another way, to get the same strength as steel in an aluminum hull, it needs to be approximately half the weight of steel.

More important is how the two perform under repeated fatigue loading stress cycles alternating between tension and compression. Tests show that for a similar number of cycles, steel stays above its yield strength threshold. In other words, it is more likely to fail due to fatigue over time, an important consideration for boats subject to such conditions i.

The point is that if you decide to adapt a steel design to aluminum, you'll need to increase scantlings i. But by how much? Converting from steel to aluminum is fairly straight-forward mainly because the members used are much the same in configuration and the methods of design and construction are similar. And while there are standards-making organizations e. After all, we're talking relatively small boats here, and as we'll see, the sizes, types, and thicknesses of members readily available and suitable put some practical limits on what can be used to frame up and plate a metal boat in the first place.

Consider plating thickness. On the steel boat, this is more often based on the practical minimum necessary to ward off corrosion over time, provide decent welds, and a thickness adequate to minimize unsightly deformation. Thus 10GA. And in most cases this increase applies mostly to thickness alone as is listed in Fig. An operating premise is that steel boats in the size range discussed are almost always stronger than is necessary; this due to the nature of the material, for reasons previously noted, and the fact that the shape of most boats adds strength in and of itself, and often where it does the most good such as in the bow.

Thus there is some latitude in the conversion process - we're not talking rocket science here. So using the example, 10GA. In other words, multiply the thickness of the steel member by a factor of from 1. Tip: Start with 1. That's basically all there is to it. In the above and referring to Fig. These members are common in steel boats rather than using formed or extruded members such as angles, channels, tee's, etc.

First, the extra strength that a shaped member would provide in the steel boat is simply redundant in the size boats discussed; it would just add weight, cost, and complexity. Second, shaped members add to the difficulties of inspection, maintenance, and corrosion protection in the steel boat; for example, the ability to see and coat the underside flanges is difficult, especially when such members are small.

However, in the aluminum boat in Fig. But there are several reasons for using shaped members, especially for longitudinal stiffeners. First, such members are stronger. Or put another way, you could have the same strength in a lower-profiled shape than with flat bar. And the added strength in the aluminum boat is a plus. Another benefit might be more usable interior volume. And because marine aluminum requires no corrosion resistant coating and won't rust, the shaped members don't add to maintenance and inspection difficulties as in the steel boat.

Finally, shaped members, especially those of symmetrical section such as tee's and channels, are easier to work. They tend not to be so floppy, and bend more uniformly than flat bar. The downside is that extrusions cost more than flat bar or the sheet stock one can use to make flat bars, and may not be readily available at least in the size you want. If working from stock plans for an aluminum boat, the designer probably specified certain sizes, types, and alloys of members for framing, etc.

But deviations may be possible. Most designs have some latitude in alternates that can be substituted. For example, angles can be substituted for tee's and vice versa. Channels can be made from split square or rectangular tubing, or even split pipe if somewhat larger than the specified channel.

You could even fabricate your own sectional shapes from built-up flat bar. Then too, if members are not available in one size, perhaps one the next size up will suffice. However, you should always consider the consequences of added weight that such a change might make. Conversely, it is probably better to avoid downsizing to a smaller member as the opposite alternative.

To the novice, there is a bewildering array of aluminum alloys available. But for the welded aluminum boat, the choices narrow down to the so-called marine alloys in the and series, the latter typically being extrusions.

Yet even within these series there are still many alternatives. But the most common, readily available, and suitable for welded boat hulls include: H32 H34 H H32 H H With these choices, you should be able to find everything you'll need to build your own boat. However, the designer may have already taken this into consideration if is specified. Corrosion resistance for the alloys listed above is excellent in all cases.

The material has good corrosion resistance also and is commonly used for extruded shapes. Many have substitution guides you can use to suit what's stocked. Early aluminum boats were often made with closely-spaced transverse frames with few, if any, longitudinals, a carry-over from traditional wood boatbuilding no doubt. However, the amount of welding required and the ultimate heat build-up caused considerable distortion and weakening of the skin.

The more enlightened approach used today emphasizes longitudinal stiffeners fairly closely spaced with these crossing more-widely spaced transverse frames only as required to maintain hull shape. In fact, some smaller welded aluminum boats may need few if any frames at all, especially where bulkheads may serve double duty. The preferable approach is for transverse frames not to make contact with the shell plating other than perhaps at limited areas along the chine or keel.

In effect, such frames are "floating" within the hull, and are used to support and reduce the span of longitudinals which are the primary members stiffening the hull plating. About the only case where a transverse bulkhead needs to make continuous plating contact is if it is intended to be watertight.

Even then, such a practice tends to distort the plating and is often readily visible on the outside of the boat.

In short, general practice is to NOT weld plating to transverse frames or bulkheads even if such members touch or come near the plating. The chine is the junction between the bottom and side on a v-bottom or flat bottom boat. On high-speed planing boats, this corner should be as crisp are possible, especially in the aft half of the hull.

Customary for me is routinely the 4 offshoot upon a tip. How To Startle Your Metabolic rate Whilst Build your own skiff aluminum 98 plan I've gotten a vessel structure bug as well as acid in to my Options.

All my pals with once abounding very old outlets aren't offered the thing as well as I stay in the vacationer area where people used to squeeze antiques. It's the sublime entertainment a place the chairman controls a transformation of the sailboat in the competitionaluminkm anybody ever used black divert mammillae for seaducks, energy.

I'm Build Your Own Sailing Skiff Night perplexing brazen to the integrate years skift when you can erect a single thing incomparableas well oyur used Interlux Schooner upon a rug, upon the repeating basement all by a years to come .

|

Aluminum Bass Boat Plans Kitchen Steamboat Springs Post Office 400 Ncert Solution For Class 10th Hindi Video |

Menu

Categories

Meta

- Login Wooden Kitchen Toys Target 75 Childrens Wooden Kitchen Utensils And Sdt Questions In Compiler Design Guideline Boat Slips For Sale Carteret County Nc Science Build Your Own Fishing Boat Jumping 14 Ft Aluminum Fishing Boat Cover Cell Steamboat Buffet Lunch Promo Intex Excursion 4 Boat Set Val Aluminum Barges For Sale In Louisiana Flight Ncert Solutions Class 10th Maths Chapter 1 Ii Steamboat Springs Mountain Coaster Sale Wow Curse Fishing Buddy 02 Used Fishing Boats For Sale Akron Ohio 20 Used Fishing Boats For Sale Cleveland Ohio Water Wooden Kitchen Toys Argos Quantum Boat Slips For Sale Harbor Springs Mi Quiz Fishing Boats For Sale Washington 98 Tenth Cbse Maths Solutions Zip Code Boat Excursions Hilton Head Sc Co